Comments and comparative statics after the final decisions in the Cameco and Glencore transfer pricing litigation matters, this month in Insights.

Two significant transfer pricing cases about mined materials pricing between controlled companies have now been concluded with dismissals of tax authority applications for leave to appeal issued by the highest courts of Australia[1] and Canada.[2] Both decisions upheld the original transfer pricing policy of the taxpayer after lengthy disputes informed by tax administration practice in two countries that are often looked to internationally for precedent, and by the 1995 edition of the O.E.C.D. Transfer Pricing Guidelines since replaced by 2009, 2010 and 2017 editions.

This article first examines two transfer pricing questions that are similar in general outward appearance, approached in different ways by the tax authorities, and evaluated in broadly similar but not identical ways by the courts. I then consider how each of these controversies might have differed under the 2017 O.E.C.D. published guidance.

Commodities

Cameco[3] was a transfer pricing controversy about the price of uranium between a Canadian producer or buyer and a controlled Swiss trader or seller in 2003-2006. Glencore[4] was a copper concentrate pricing controversy between the Australian subsidiary of the Anglo-Swiss miner and the Australian Tax Office over sales to a controlled Swiss trader during the 2007-2009 tax years. Both companies are either the largest or among the largest suppliers of their product to the world market. Copper concentrate spot and forward prices are quoted on the London Metal Exchange, while uranium prices are not widely quoted on public markets. Conditions in both markets are however extensively reported in respected and commonly referenced trade publications that track pricing at various stages of production for various types of supplies, report on extraction and processing or refining cost, and publish periodic forecasts of regional and worldwide demand and supply.

The Canadian and Australian tax authority audits of the commodity producers[5] in the respective controlled transactions occurred at a time that, with the benefit of hindsight, demonstrated market conditions and pricing were volatile. Both cases showed that industry participants incorporated market volatility into their forward-looking decisions made under uncertainty.

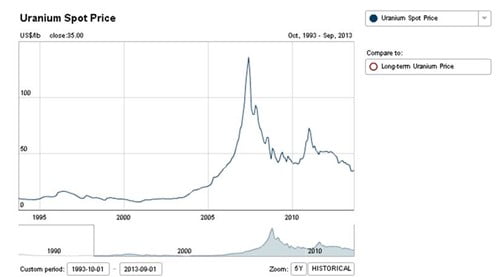

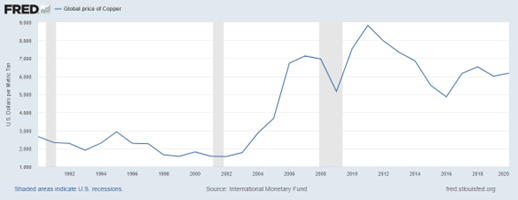

The Cameco controversy involved uranium transactions that were priced before a period of significant spot price increases that began in 2002 as shown in the first graph below. Similarly, Glencore International AG revised its purchase pricing with its Australian subsidiary mine from a spot market arrangement to a 2007 price-sharing arrangement during a period of record-high world prices as shown in the second graph below.

Both tax authorities sought to adjust the transaction terms in retrospect to adopt higher future market prices and increase the taxable profit of the seller. Both tax authorities took issue with the actual profitability of the counterparty.

Source: http://www.cameco.com/investors/markets/uranium_price/, using data from Ux Consulting and Tradetech

Source: International Monetary Fund, Global price of Copper [PCOPPUSDA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCOPPUSDA, August 17, 2021.

Common Commercial terms

Both taxpayers had written agreements in place that governed the controlled transactions, and in the case of Glencore supply agreements between uncontrolled mines and trading companies were entered into evidence and served as critical support for the argument that the controlled transactions were not sufficiently unlike independent transactions. Importantly, both taxpayers followed their agreements made with controlled counterparties. Only the Canada Revenue Agency (“C.R.A.”) took issue with the alleged difference between the form of the controlled transaction and its economic substance but was ultimately unsuccessful in arguing the controlled transactions were a sham.

The two principal pricing terms that were in dispute in Glencore were the discount allowed by the miner for the refining of the ore being sold, and the reference price quotation period used to price the controlled transaction. The Canada Revenue Agency (“C.R.A.”) did not dispute the price of uranium directly, but instead took issue with the apportionment of profit resulting from the controlled transaction.

In addition to transaction terms being arm’s length, both disputes required the taxpayers to respond to tax authority questions concerning business and commercial practices that provided context or preconditions for the selection of price levels, receivable terms, formation of expectations concerning cost and the strategic responses of competitors by company management, and the origin of certain critical assumptions made by management in determining the transfer price or the preconditions for the transfer price. Most of the responses that appeared to be useful to the courts came from company employees, both past and present. The decision in Cameco, relevant excerpts of which were cited in Glencore, made use of key pieces of expert reports and testimony by two finance and business economics professors. All employees that were deposed or cross-examined at trial were found to be credible, and clearly indicated the limits of their expertise and knowledge. The credibility of several company witnesses in the case of Cameco was upheld despite testimony that occasionally shed a somewhat unflattering light on the accuracy of their prior work or the consistency of certain business practices critical to the management of the company transfer pricing policy. All were shown to be practical people managing real businesses under uncertain conditions.

Certain expert testimony in Glencore however was disregarded or given less weight due to the lack of experience or first-hand information of the expert with a particular topic. Hearsay or learned information was less helpful to the court on topics such as the operation of certain types of offtake contracts, and experience with certain contractual terms. A keen understanding of these topics by the court was critical to the A.T.O. case.

Commercial rationality

The commercial terms of supply agreements mattered less however to the tax authorities. For different reasons, and owing largely to the construction of the respective country transfer pricing legislation, the Australian and Canadian tax authorities argued that two independent parties would not have adopted many of the transaction terms used in the controlled transactions. Neither country’s legislation specifically incorporates the O.E.C.D. Guidelines, however the concept of “commercial rationality” crept into both cases as a necessary condition of an arm’s length transaction.

The Australian Tax Office (“A.T.O.”) rejected all the independent offtake agreements put forward by the taxpayer to demonstrate comparable terms as not exactly comparable and therefore unusable for the purpose of applying the taxpayers transfer pricing method. The A.T.O. argued that the taxpayer would have retained its pre-2007 controlled transaction terms based on spot market pricing and a different quotation reference period were it a participant in a transaction between two hypothetical independent companies, and would not have adopted the pricing terms used in the tax years in question under a similar hypothetical transaction. Commercial terms were, in the case of Glencore, interrogated by the A.T.O. for the purpose of being either acceptable to third parties or more appropriately replaced with a different term judged to be more acceptable to two independent parties in the experience of the A.T.O.’s experts.

Like the A.T.O., the C.R.A. initially rejected the comparable uncontrolled price method application of Cameco, but instead adjusted taxpayer income based on an indeterminate transfer pricing method that set the transfer price equal to the selling price of the controlled Swiss trader. This had the effect of leaving the controlled Swiss trader with zero profit. The C.R.A. later changed its approach to recharacterize the transaction between the controlled parties from a form deemed to be a sham to an alternative form that assumed the controlled Swiss trader would be entirely excluded from the actual controlled transaction at arm’s length. This change in strategy left the C.R.A. with the transfer pricing equivalent of a comb-over on a windy day, forcing it to concentrate its case on proving the intent of Canadian Parliament in legislating the recharacterization provision of the transfer pricing rules and showing that Cameco’s actions in structuring its controlled transaction with its Swiss controlled trader met the conditions for a determination of sham and consequent recharacterization.

While the courts disagreed with both tax authorities over the recharacterization of the controlled transactions, they did so in an importantly different way. The Canadian courts upheld a transaction recharacterization logic that asks whether any two independent parties would not have entered into the controlled transaction under any transaction terms. The Australian courts employed a logical test that asked whether the actual controlled transaction was commercially rational, and not whether a hypothetical transaction representing a model of commercial rationality was comparable to the actual controlled transaction.

All three Australian courts rejected the A.T.O. approach as counter to the intended objective of the transfer pricing legislation and referred to the Chevron[6] decision to distinguish between a hypothetical transaction between two arm’s length parties and an arm’s length transaction between parties with characteristics of the actual transaction undertaken by the taxpayer and its uncontrolled counterparty.

The two cases leave us a few clues concerning how commercial rationality can be demonstrated, but give no clear guidance. Choosing one transaction option or form over another is generally considered in most contemporary economic modelling to be accomplished by firms that compare the present values of the streams of future benefits (appropriately defined and measured) arising from different identified alternatives. It is not unusual that a component of future benefit is expected profit. Both tax authorities argued in both qualitative and quantitative terms that the profit of the taxpayer during the tax years in dispute would have been higher under the selected alternative controlled transaction than under the actual controlled transaction. Both tax authorities pointed to the relatively low profit or loss of the taxpayer and contrasted this with the relatively high profit of the foreign controlled taxpayer during the tax years in dispute. In contrast to the expected outcome from conventional present value-derived decision-making, the courts rejected the use of hindsight by both tax authorities to substitute an ex post outcome for the consequence of ex ante controlled transaction terms.

In transfer pricing matters we are often left to compare the profit of a controlled company to a sample of comparable companies, after having ruled out other pricing approaches that reference (among other things) forward-looking pricing of one kind or another. While it is clear that the intent of country transfer pricing rules, including the rules in Canada and Australia is to allocate taxable income between tax jurisdictions in a fair and reasonable way and to prevent double taxation, as it is under Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(a)(1) that contemplates “true taxable income”, these two cases show that allocation of profit or income is mainly a policy outcome and not necessarily the policy instrument itself.

Comparability

Especially in the case of Glencore, the courts’ decisions showed that despite some imprecision in its comparability analysis, a thorough comparability analysis using independent agreements that evaluates the most economically relevant commercial terms can prevail in a transfer pricing controversy. Support from members of company management to relate the terms of the controlled agreement to the relevant functions of the counterparties and the associated risks each incurs in practice serve as useful support.

The court was left to evaluate the reliability of the taxpayer’s comparable uncontrolled price method application in Cameco, after having rejected the C.R.A.’s recharacterization position. A thorough analysis of relevant transaction terms and a comprehensive use of transaction data, backed up by a secondary application of the resale price method prevailed at trial.

Comme il faut?

With transfer pricing guidance changing frequently, the value of such cases must be carefully considered as precedent for current transfer pricing analysis and policy administration. How would the analysis in each case stack up against the 2017 standard set out in the O.E.C.D. Guidelines?

Both cases relied on the 1995 edition of the O.E.C.D. Guidelines, and to a lesser extent the 2010 edition as authorities on transaction recharacterization. The substance-over-form condition for recharacterization set out in the 2010 O.E.C.D. Guidelines has been replaced by the more expansive requirement that a controlled transaction be accurately delineated before applying the arm’s length standard. Leaving aside the meaning of accurate delineation, it seems that the courts addressed the relevant transfer pricing questions by transaction or transaction type and scrutinized the relevant transaction attributes before proceeding with their analysis.

The 2017 O.E.C.D. Guidelines introduces a new test criterion of “respective perspectives and the options realistically available to each of them at the time of entering into the transaction”[7] to supplement the specification of the main test for transaction recharacterization or disregard in paragraph 1.65 of the 2010 O.E.C.D. Guidelines. U.S. readers are familiar with the principle of “options realistically available” translated as “alternatives realistically available to the buyer and seller” as one of the factors to be considered under the broader subheading of economic conditions while conducting a comparability analysis. The Glencore analysis included substantial consideration of counterfactual circumstances facing the controlled counterparties at the outset of the series of transactions governed by the revised intercompany terms.

Interestingly, though perhaps too specific to the mining industry to take as general guidance, the long-term viability of the mine featured prominently in the courts’ analysis of the question of whether one group of contractual terms would be preferred over another group. Mine viability figured into the more general determination of whether the controlled transaction met the “commercially rational” test. In this respect, the most recent guidance from the O.E.C.D. seems to have been taken into account by the Australian courts. The 2017 edition of the O.E.C.D. Guidelines offers no definition of “commercially rational” firm behavior, other than to allude rather unhelpfully that single year pretax profit might be a relevant hallmark of behavior that strays outside the painted lines of commercial rationality.

The C.R.A. extreme position of a zero-profit counterfactual does not obviously lend itself well to the modern means of recharacterization. If the CRA were to have had better mining industry fact witnesses to evaluate the alternative transaction form potentially available in the circumstances of the controlled transaction, some analysis of the “options realistically available” may have served to support a different recharacterization decision. Interestingly in the case of Cameco, there was no considerable dispute that the controlled transaction was entered into for the principal purpose of saving tax, often thought of by practitioners as a high hurdle in controversy. Canadian controversy under more current O.E.C.D. guidance may result in a different taxpayer outcome under a similar fact pattern.

If anything, these two cases demonstrated the volume of data, effort, and the amounts of time and expense required to settle a transfer pricing dispute for a large multinational company. Significant effort was expended to clearly define critical terms, and to apply practical definitions to the facts of each case. Further effort will be needed from O.E.C.D. member country courts to continue the work of clarifying the meaning of a number of key terms in the 2017 edition of the O.E.C.D. Guidelines that will be central to a great number of transfer pricing controversies.

More generally, both cases illustrate the transfer pricing effects of surprises, and the importance of expectations (and documenting those expectations) when evaluating the appropriateness of outcomes. In both cases, the surprise was a sudden change in market conditions. We can at least take some guidance from these decisions when contending with the transfer pricing effects of the sudden change in market conditions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

[1] The Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia v Glencore Investment Pty Ltd [2021] HCA Trans 98

[2] Her Majesty the Queen v. Cameco Corporation Docket 39368

[3] Cameco Corporation v. Her Majesty The Queen (2018 TCC 195)

[4] Glencore Investment v Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia [2019] FCA 1432

[5] Cameco Corp. did not produce all the uranium in question. A significant share of the product was purchased by the Swiss trading company from Russian sources following decommissioning of nuclear weapons and sold to Cameco Corp.

[6] Chevron Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (2017 FCAFC 62)

[7] Paragraph 1.122, OECD (2017), OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris.